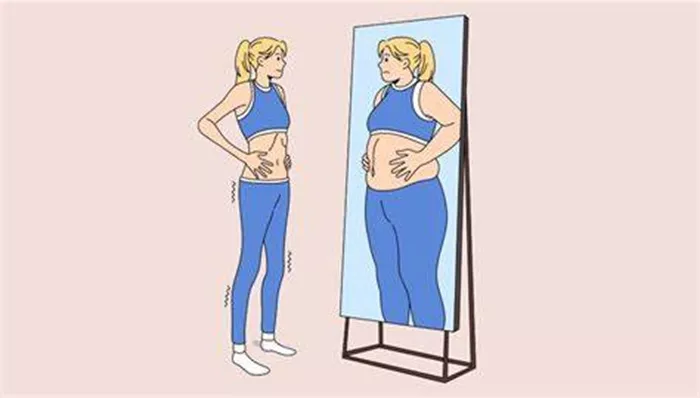

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), commonly referred to as body dysmorphia, is a mental health condition characterized by an obsessive focus on perceived flaws in physical appearance, which are often unnoticeable to others. This preoccupation can lead to severe emotional distress and impede daily functioning. Understanding the causes of body dysmorphia in the brain is critical for developing effective treatments and support strategies. This article explores the neurological, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to body dysmorphia.

The Neurological Basis of Body Dysmorphia

Recent research has increasingly pointed towards specific abnormalities in brain function and structure that may underlie body dysmorphia. Understanding these neurological underpinnings is essential for a comprehensive grasp of the disorder.

Brain Structure Abnormalities

Studies using neuroimaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have revealed that individuals with BDD often exhibit structural differences in certain brain regions. The most consistently implicated areas include the orbitofrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the visual cortex.

Orbitofrontal Cortex: The orbitofrontal cortex is involved in decision-making and evaluating the emotional significance of events. Abnormalities in this area may contribute to the heightened negative emotional response to perceived physical flaws.

Amygdala: The amygdala plays a crucial role in processing emotions. In people with BDD, heightened activity in the amygdala may lead to increased anxiety and distress when they view their own bodies.

Visual Cortex: The visual cortex processes visual information. Studies have found that individuals with BDD have abnormal activation patterns in the visual cortex, which may affect how they perceive their physical appearance.

Neurochemical Imbalances

Neurotransmitters, the brain’s chemical messengers, also play a significant role in BDD. Imbalances in certain neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin, have been associated with the disorder.

Serotonin: Serotonin is involved in mood regulation and has been linked to obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Lower levels of serotonin may contribute to the obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors seen in BDD.

Dopamine: Dopamine is associated with reward and pleasure. Abnormal dopamine activity may affect the reward system in people with BDD, leading to an exaggerated response to perceived flaws and reinforcing negative self-evaluation.

Cognitive Processes and Perceptual Distortions

Cognitive and perceptual distortions are central features of BDD, where individuals misinterpret or exaggerate minor or non-existent physical flaws. Understanding these distortions is key to addressing the disorder.

Attention Biases

People with BDD often display an attention bias towards their perceived defects. They tend to focus excessively on specific body parts they believe to be flawed, which reinforces their negative self-perception. This attentional focus can be measured using eye-tracking technology, revealing that individuals with BDD spend more time looking at their “flawed” areas compared to healthy controls.

Perceptual Distortions

Perceptual distortions in BDD may result from abnormalities in visual processing pathways. Individuals with the disorder often report seeing their perceived defects as more prominent and severe than they actually are. This misperception can be linked to dysfunctional neural circuits in the visual cortex and related brain areas responsible for integrating visual information.

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases, such as selective attention to negative information and overestimation of the impact of perceived flaws, further perpetuate body dysmorphia. These biases are often reinforced through cognitive processes like rumination and catastrophic thinking, where individuals magnify the importance and consequences of their perceived defects.

Psychological and Environmental Triggers

While neurological factors provide a foundation for understanding BDD, psychological and environmental triggers play a crucial role in the onset and maintenance of the disorder. These factors interact with the brain’s vulnerabilities to create a complex web of influences.

Early Life Experiences

Early life experiences, particularly those involving appearance-related teasing, bullying, or criticism, can significantly impact the development of body dysmorphia. Children who are frequently subjected to negative comments about their appearance may internalize these criticisms, leading to long-lasting self-esteem issues and body image concerns.

Parental Influences

Parental attitudes towards body image and appearance can also shape an individual’s self-perception. Parents who place a high value on physical appearance or who are overly critical of their child’s looks may inadvertently contribute to the development of body dysmorphia. Additionally, parents who model unhealthy behaviors, such as excessive grooming or dieting, can reinforce the importance of appearance in their children.

Cultural and Societal Pressures

The cultural and societal emphasis on physical appearance, particularly in Western societies, can exacerbate body dysmorphia. Media portrayals of idealized beauty standards create unrealistic expectations that many individuals feel pressured to meet. Social media platforms, with their focus on visual content and often digitally altered images, can intensify these pressures by constantly exposing individuals to comparisons and judgments.

Personality Traits and Psychological Factors

Certain personality traits and psychological factors can increase susceptibility to body dysmorphia. Perfectionism, for example, is a common trait among individuals with BDD. Perfectionists often set unattainably high standards for themselves, leading to constant dissatisfaction with their appearance. Other psychological factors, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies, can also contribute to the development and maintenance of body dysmorphia.

See Also: How Long Does Skeeter Syndrome Swelling Last?

The Role of Genetics in Body Dysmorphia

Genetics may also play a role in the development of BDD. While no specific gene has been identified as the cause of body dysmorphia, research suggests that genetic factors contribute to the disorder’s heritability. Understanding the genetic underpinnings can provide insights into why some individuals are more predisposed to developing BDD than others.

Genetic Predisposition

Family studies have indicated that body dysmorphia tends to run in families, suggesting a genetic component. First-degree relatives of individuals with BDD are more likely to develop the disorder compared to the general population. Twin studies further support this genetic link, showing higher concordance rates for BDD in monozygotic (identical) twins than in dizygotic (fraternal) twins.

Gene-Environment Interaction

The interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors is crucial in understanding the development of body dysmorphia. While genetics may create a vulnerability to BDD, environmental triggers, such as childhood trauma or societal pressures, often play a pivotal role in the onset of the disorder. This gene-environment interaction highlights the complexity of BDD and underscores the need for multifaceted treatment approaches.

Psychological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions

A comprehensive understanding of body dysmorphia requires examining the psychological mechanisms that sustain the disorder and the therapeutic interventions that can address these mechanisms. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be particularly effective in treating BDD.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT focuses on identifying and challenging the distorted beliefs and cognitive biases that underpin body dysmorphia. This therapy helps individuals develop healthier ways of thinking about their appearance and reduces the compulsive behaviors associated with BDD.

Cognitive Restructuring: This technique involves challenging and reframing negative thoughts about one’s appearance. By identifying irrational beliefs and replacing them with more balanced perspectives, individuals can reduce their preoccupation with perceived flaws.

Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP): ERP is a critical component of CBT for BDD. It involves gradually exposing individuals to situations that trigger their body image concerns while preventing them from engaging in compulsive behaviors, such as mirror checking or excessive grooming. Over time, this exposure helps reduce anxiety and distress associated with their appearance.

Mindfulness and Acceptance Strategies: Incorporating mindfulness and acceptance strategies into CBT can help individuals develop a more accepting attitude towards their appearance. Mindfulness techniques, such as meditation and mindful breathing, can reduce the focus on negative thoughts and increase overall emotional well-being.

Pharmacological Treatments

In addition to CBT, pharmacological treatments can be effective in managing body dysmorphia. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed to individuals with BDD, as they help regulate serotonin levels and reduce obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

SSRIs: SSRIs, such as fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Zoloft), have been shown to alleviate the symptoms of BDD by increasing the availability of serotonin in the brain. These medications can reduce anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors, making them a valuable component of a comprehensive treatment plan.

Conclusion

Body dysmorphic disorder is a complex and multifaceted condition influenced by neurological, psychological, and environmental factors. Abnormalities in brain structure and function, neurochemical imbalances, cognitive and perceptual distortions, early life experiences, cultural pressures, and genetic predispositions all contribute to the development and maintenance of BDD. Understanding these factors is essential for developing effective treatments and support strategies.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, pharmacological treatments, and a multidisciplinary approach to care offer promising avenues for managing body dysmorphia. Future research should continue to explore the neurological and genetic underpinnings of the disorder, paving the way for more targeted and personalized treatment approaches. By addressing the complex interplay of factors that contribute to body dysmorphia, we can help individuals achieve a healthier and more positive body image, improving their overall quality of life.

[inline_related_posts title=”You Might Be Interested In” title_align=”left” style=”list” number=”6″ align=”none” ids=”9883,9839,9822″ by=”categories” orderby=”rand” order=”DESC” hide_thumb=”no” thumb_right=”no” views=”no” date=”yes” grid_columns=”2″ post_type=”” tax=””]