A groundbreaking study has uncovered a new method of analyzing human tooth enamel that could significantly advance our understanding of ancient human health. Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the research highlights two immune proteins embedded in enamel: immunoglobulin G (IgG), which fights infection, and C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation. This innovative approach may offer unique insights into the health and stress levels of past populations, opening doors to new interpretations of historical human experiences.

Key Immune Proteins in Tooth Enamel

The research team, led by Tammy Buonasera, an assistant professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, explored how immune proteins trapped in tooth enamel could be used to study the health of ancient human populations. Immunoglobulin G is a key antibody produced during infection, while C-reactive protein signals inflammation. Both of these proteins, embedded in enamel, are resilient enough to be preserved for thousands of years, offering researchers a novel way to study disease and health in the past.

“This is the first time immune proteins in enamel have been analyzed, and it opens up a new method for investigating historical and prehistoric health in a more targeted way,” said Buonasera.

The Study: Populations Tested

The research initially began during Buonasera’s tenure as a research associate at the University of California, Davis, in collaboration with local Indigenous tribes. The team analyzed tooth enamel samples from three distinct groups:

Ancestral Ohlone People: Teeth from Indigenous people buried in the San Francisco Bay Area, dating back to the late 1700s and early 1800s. These remains were uncovered during a construction project in 2016, and descendants of the tribe gave their permission for the teeth to be studied.

European Settlers: Individuals from the late 1800s who were buried in a San Francisco cemetery.

Modern Military Cadets: Present-day wisdom teeth donated by cadets, serving as a contemporary comparison group.

By comparing protein levels in the teeth of these three populations, researchers aimed to connect stress and disease markers with historical records of each group’s experiences. Native Californians from the mission era faced extreme stress, disease, and high mortality rates. In contrast, the European settlers, while living shorter lives than modern populations, were presumed to have experienced less stress and disease. The military cadets were considered to have the best health and nutrition among the groups.

Findings: High Stress in Indigenous Populations

The study revealed that the Indigenous Ohlone people had significantly higher levels of both immune proteins compared to the other groups, reflecting the high levels of stress and disease they faced. In particular, the children’s teeth showed elevated levels of immunoglobulins and C-reactive proteins, indicating frequent exposure to infections and intense stress.

“It’s heartbreaking to see such high levels of immune responses in children, especially when you consider the challenges they faced—disease, cultural displacement, and the loss of family members,” said Jelmer Eerkens, anthropology professor at UC Davis and a co-author of the study.

Teeth as Historical Health Records

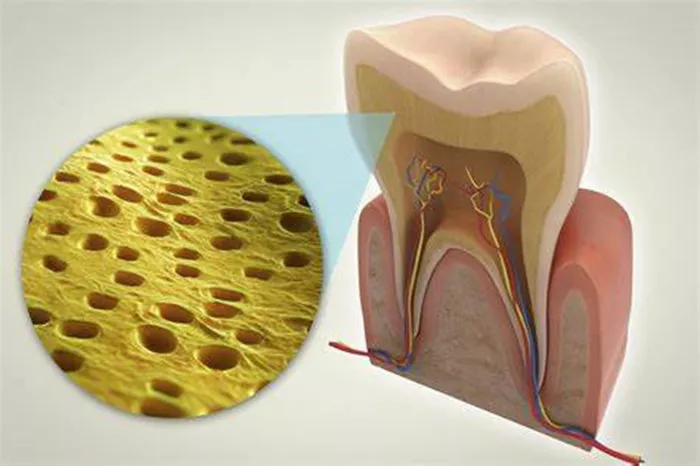

Buonasera explained that this new method could revolutionize how scientists interpret human history, as tooth enamel offers a unique biological record of an individual’s health throughout their development. Teeth begin forming in utero and continue growing through adolescence, much like the rings of a tree, capturing details about a person’s immune system responses over time.

This new technique also allows scientists to gather more specific health data than from skeletal remains alone. While many illnesses do not leave visible marks on bones, immune proteins in teeth can reveal details about past infections and inflammation.

Another advantage is the durability of tooth enamel, which preserves proteins far longer than other tissues. This means that researchers can examine teeth from ancient humans and potentially build a timeline of health stretching back thousands of years.

Modern Applications

While the research offers valuable insights into ancient human health, Buonasera noted that it could also provide relevant comparisons to modern health and lifestyles.

“By understanding the stress and immune responses in ancient populations, we can potentially learn more about the effects of stress and disease on modern human health,” she said.

The study not only represents the first analysis of immune proteins in enamel but also showcases the precision of the method. According to co-author Glendon Parker, an adjunct associate professor at UC Davis, the technique could have broad applications in bio-anthropology and beyond.

“These new tools provide an exciting opportunity to gain deeper insights into the lives of past populations,” Parker said. “This approach has the potential to address many questions about human health, both ancient and modern.”

As new methods continue to develop in this field, the study marks an exciting time for research into the intersections of anthropology, biology, and health.

[inline_related_posts title=”You Might Be Interested In” title_align=”left” style=”list” number=”6″ align=”none” ids=”9301,6547,6532″ by=”categories” orderby=”rand” order=”DESC” hide_thumb=”no” thumb_right=”no” views=”no” date=”yes” grid_columns=”2″ post_type=”” tax=””]